Introduction to Mesa

25 May 2016 | mesa, linux, graphicsI have been working on video post processing on mesa for the past two weeks, So I thought I could also write about it and it might help someone who wants to contribute to mesa. Hence, I will be doing a series of post regarding mesa, linus grahics stack ,video processing and more. This is the first post in a series of posts to come. It will serve as a introduction to mesa and the linux graphics stack.

To understand the role of mesa and X Windows System in its current state we need to look at history of linux graphics stack and its evolutions over the years.

X Windows System

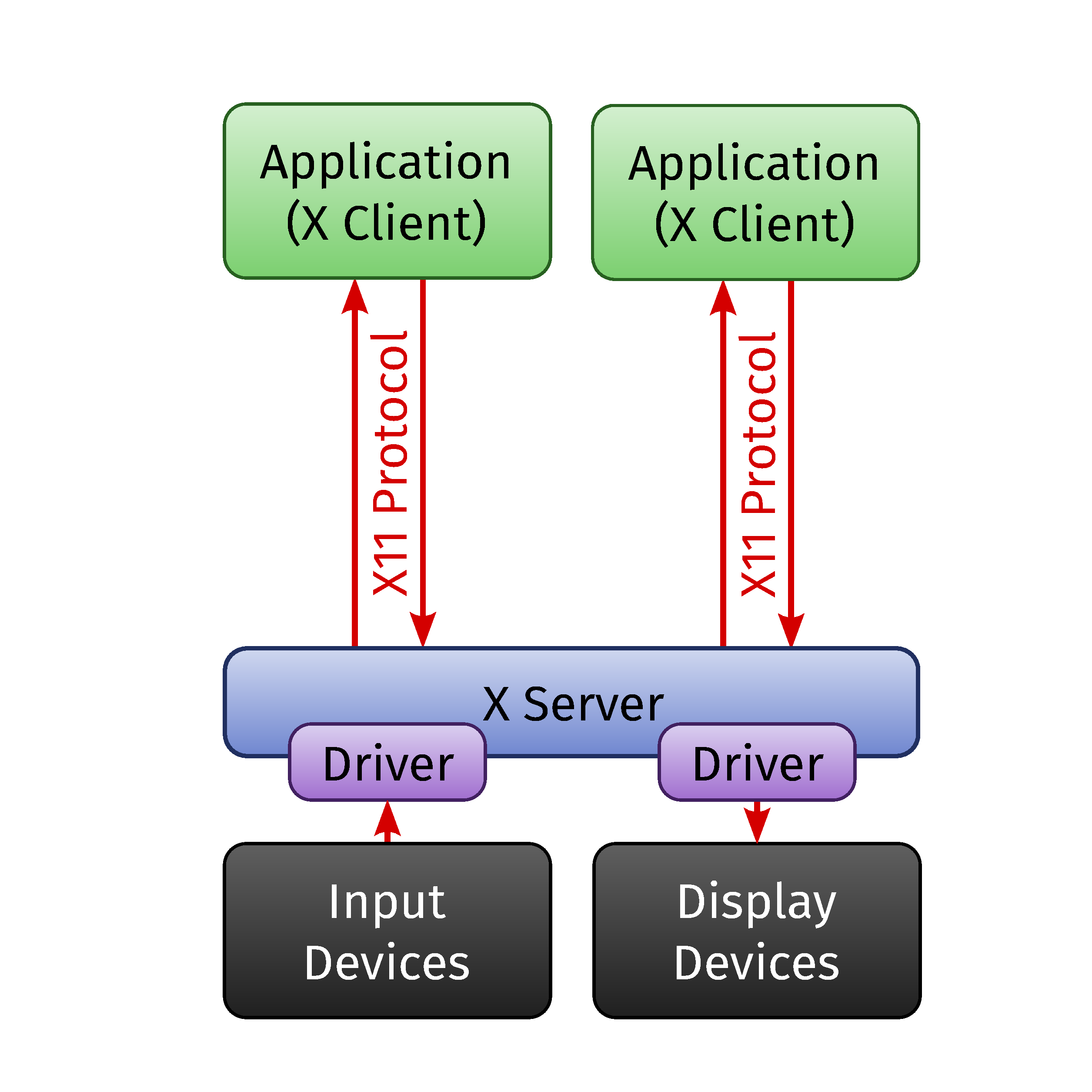

To display something on the screen all graphics cards generate a “frame buffer”, ie a block of memory with 3 bytes per pixel, being the RGB color to show at that pixel on the screen. One frame-buffer known to the graphics card is the “scan-out buffer”, ie the one that will be displayed. X Windows System has a X Server which does the job of drawing the frame-buffer for different X Clients. The X Clients follow a protocol to give instruction to X Server as to what needs to be displayed. This protocol is called the X11 protocol.

X Server manages a window hierarchy:

- root window = desktop wallpaper

- top-level windows = application windows

- subwindows = controls (buttons etc.)

X Clients don’t implement the X11 protocol directly, but use libraries like Xlib or XCB. Toolkits like Gtk, Qt use Xlib or XCB internally to display applications. A Windows Manager is a special that manages the positions of the top-level windows and draws frame around them. X Server also manages the input from keyboard, mouse and other input devices.

This is very good tutorial on X Windows System. It covers different aspects of X in a interactive way.

OpenGL

The above covers 2D graphics as that is what the X server used to be all about. However, the arrival of 3D graphics hardware changed the scenario significantly, as we will see now. It led to creation of a standard API. Open Graphics Library (OpenGL) is a application programming interface (API) for rendering 2D and 3D vector graphics. The API is typically used to interact with a graphics processing unit (GPU), to achieve hardware-accelerated rendering.

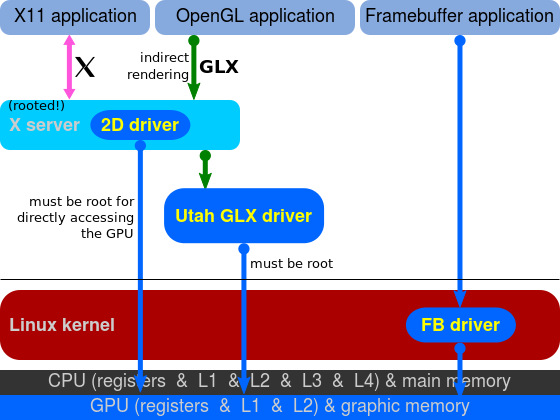

However, in a system where only the X server was allowed to access the graphics hardware we could not have a openGL implementation that talked directly to the 3D hardware. Instead, the solution was to provide an implementation of OpenGL that would send OpenGL commands to the X server through an extension of the X11 protocol and let the X server translate these into actual hardware commands as it had been doing for 2D commands before. We call this Indirect Rendering, since applications do not send rendering commands directly to the graphics hardware, and instead, render indirectly through the X server.

But developers would soon realize that this solution was not sufficient for intensive 3D applications, such as games, that required to render large amounts of 3D primitives while maintaining high frame rates. To achieve good performance using 3D hardware, we need to allow direct access to hardware.

DRI

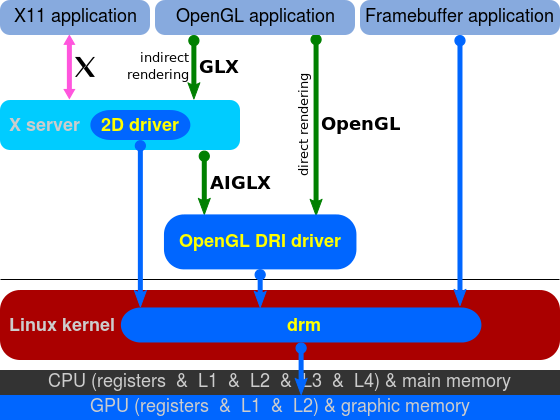

As developers realized that indirect rendering can’t handle intensive 3D application, efforts to allow direct access to hardware started, resulting in direct rendering infrastucture (DRI). DRI is the new architecture that allows X clients to talk to the graphics hardware directly. Implementing DRI required changes to various parts of the graphics stack including the X server, the kernel and various client libraries.

To allow X client to directly interact with hardware we need Direct Rendering Manager (DRM). DRM provides X Clients a API through which they can use the 3D hardware. DRM is a part of the kernel and interacts with the GPU. DRM has GPU specific code to implement rendering.

DRI/DRM provide the building blocks that enable userspace applications to access the graphics hardware directly in an efficient and safe manner, but in order to use OpenGL we need another piece of software that, using the infrastructure provided by DRI/DRM, implements the OpenGL API while respecting the X server requirements.

Enter Mesa

Mesa acts a link between OpenGL programs and DRI. Mesa contains implementation of the OpenGL API, which allows user to write programs without taking care of the different DRI drivers.

When our 3D application runs in an X11 environment it will output its graphics to a surface (window) allocated by the X server. Notice, however, that with DRI this will happen without intervention of the X server, so naturally there is some synchronization to do between the two, since the X server still owns the window Mesa is rendering to and is the one in charge of displaying its contents on the screen. This synchronization between the OpenGL application and the X server is part of DRI. Mesa’s implementation of GLX (the extension of the OpenGL specification that addresses the X11 platform) uses DRI to talk to the X server and accomplish this.

What’s next?

Hopefully I have managed to explain the role of mesa in the linux graphics stack. In the next post we will see how to setup mesa development environment.